There have been many breathtaking headlines about the recent Pew Research Report, particularly on the idea that Muslims are growing faster than Christians. However, even in Pew Report, Christians continue to be the largest religious segment in the world.

The faster Muslims are growing, not really that new right now.

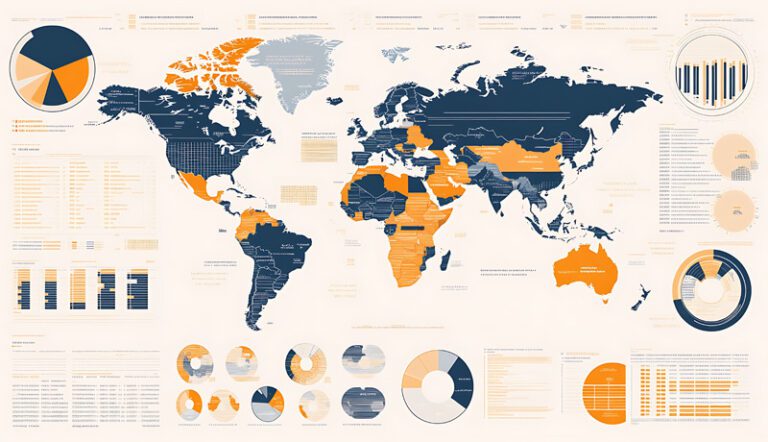

The faster Muslims are growing, not really that new right now. It has been known for a long time, and the situation in Global Christianity 2025 reaffirmed this in January. That January report showed that Islam had grown at 1.6% PA for the period from 2020 to 2025, while Christian had grown at 0.98%. But we need to keep one thing in mind. In the global South where Christianity is most competitive with Islam, Christianity has grown at 1.6%, consistent with Islam’s growth. In the global northern part of the world where Christianity competes with agnosticism, it has fallen by -0.41%, while secularism is growing globally at 0.19%.

The global number of Christians in 2020 was 2.5 billion.

When I read the Pew Report, I scratched my head, when you do mathematics, the Global Christian (CSGC) Research Center estimates the number of 2.5 billion Christians in 2020. In other words, Pew’s Christian population in 2020 is about 1/40 million (close to the US population), which is less than the global Christian database. Why is it reasonable to wonder?

Unfortunately, the two are not directly comparable in regional accumulation. Mainly, Pugh divides its numbers into sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East/North Africa, combining Asia and the Pacific, while the CSGC follows the UN treaty with Europe, North America, Africa, Asia, Latin America and Oceania. But we can combine them:

But there are still differences. why? When I dig into the Pew Report, the first thing that stood out for me was the 20-page state. “This Pew research study first reported on the observed patterns of coming and going to religious organizations at a global level.” I think it means that they are in fact the first Pew report to do so. The World’s Christian Encyclopedia and the Operation World International Prayer Guide have both done this for decades.

Still, the analysis clearly explains both natural growth and transformation (what Pew calls “religious switching”). Go past the next 140 or so pages in your report and jump directly to the 162 pages that begin with “country or regional data sources.”

All Pewsauce are census data and polls.

When you look at this, it stands out immediately. All Pews sources are census data and polls. In other words, Pew’s analysis aims only to what is called “reported” data, ignoring more realistic “partnership” data.

It’s challenging. First of all, page 20 did a big deal about “religious switching,” but if you dig into the data sources you can see 79 countries “data not available” in the switching. Certainly, many of these are small countries (such as Fiji), but also include many so-called “10/40 window” countries, as well as countries with a well-known movement towards Christ (such as Sierra Leone, for example).

If data on religious switching is available to Pew, it again comes from research, polls and census jobs.

Moving on to the 180 pages and the religious composition table, we see that most countries in the world are divided into total populations and religious proportions in 2010 and 2020. I did a quick spot check and found an estimate of the percentage of Christianity in China: 2.3% in 2010, 1.8% in 2020. The source of this is a general social survey in China.

The CSGC brings the total number of Chinese followers to over 100 million.

In a 2011 report, Pew discussed the challenges by using this number, but it’s the number he uses anyway. The CSGC brings the total number of Chinese followers to over 100 million. Others estimate it is 10% or more.

I think 2% is too low in estimate. Furthermore, saying that Chinese Christianity declined between 2010 and 2020 is something to be challenged. Most of the analysis I have seen suggests growth is tapering, but it does not mean that the number of churches is falling there.

The proportion of Christians in India was also estimated to be 2.3% in 2010 and 2.2% in 2020. I think this is an obvious underestimation. This number is based on the census and is known to have some Christians not counted for several reasons.

Operation World estimated Indian Christians at 5.8% in the previous edition. Operation World also estimates that India’s Christianity is growing at over 3% per year, and we know that many movements are growing in most of India’s non-Christian states. There is no action other than the official census that presumes Indian Christianity is declining. All other evidence is against it.

Another problematic estimate is that Iran’s Christianity has fallen from 0.2% to 0.1%. This means moving from 150,000 to 87,000 or reducing it in half in terms of percentage. Again, official government data reflects reality and varies widely from one to another by every other account.

I don’t think Pew Report is a deceptive thing, but I don’t think it’s accurate.

They did a decent job given the constraints that the Pew Report appears to have placed itself in terms of methodology and data sourcing. However, I don’t think Pew Report is a deceptive thing, but I don’t think it’s accurate.

At the global level, it has some of the same conclusions as the status of the global mission and the global Christian database, but the details of that look very unstable. If the two most populous countries in the world (China and India) have a proportion of Christian figures coloured by government census and government-influenced think tank figures, I think the rest of the reports are susceptible to a variety of similarly unattractive biases.

We strongly recommend sticking to data created annually by CSGC, drawn from global analyses from global Christian databases.

It was originally released in Justin Long’s Weekly Roundup Premium Edition. It was reissued with permission.

Justin Long has been involved in missions since 1990, beginning with the International Association of Mission Services and the World’s Christian Encyclopedia. He led the development of StrategicNetwork.org in 2000 and supported research efforts in Southeast Asia from 2004 to 2008.