The neighbour in the heart of Hanover Park is a neighbourhood carved in the flats of South Africa’s vibrant, but deeply unequal Cape Town cape, with the Rev. Craven Engel and his dedicated team standing as a beacon of resistance to the relentless tide of violence.

The community is described as “the gloomy neighbourhood of monotonous buildings and unemployed young men” by a BBC Africa documentary that recently tracked the dangerous but critical work that Rev. Engel and his team did.

Paradoxically one of Africa’s richest cities and equally one of the most unequal cities, Cape Town tackles the harsh reality of being the country’s gang capital, plaguing with a murder rate of 70 per 100,000. This harsh statistics are highlighted by the fact that 263 gang murders were reported in the Western Cape in just three months in 2024, including the deaths of 79 children due to gunshot wounds and stab wounds.

According to the BBC, gangs actively recruit children between the ages of 8 and 15, leading to a scary scenario where one child gang could be shot down an entire group of children with a gun if they had one child’s gang in it. Such widespread violence means emergency services, and police often avoid these dangerous zones and feel that residents have been abandoned.

Former Gangster building the bridge

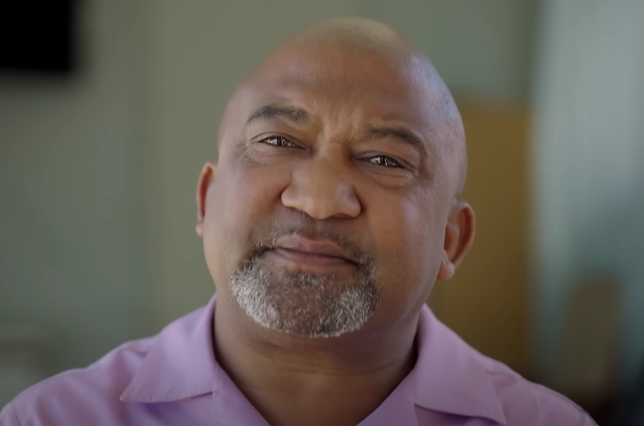

Contrary to this tragic background, Pastor Engel has established a ceasefire since 2013, an NGO that has adopted a model of community-based “violent inthrupters.” “We are driven by a mission to reduce violence within our communities so that people can be safer, children can walk to school safely, and children can play outside,” Pastor Engel said.

Rev. Engel and his team, which are particularly made up of reformed gangs, treat violence like an illness and focus on its “detection, interruption, and changing mindset.” Operated from Hanover Park’s first Community Resource Center, his team is equipped with unique equipment, consisting primarily of reformed gangs, and is named “Skillset and Experience.” As Engel explains, these intervals must be “reliable in the community. They must have changed their lives,” critically saying, “They must understand prison culture, gang culture, and gangs must respect them.”

They are on the forefront and aim to bring a measure of peace to an environment shaped by the forced removal of the apartheid era, when social control over youth was lost and drug trafficking became the “most prosperous economy.”

“Nearly 70% of our youth are obsessed with some kind of substance, either heroin or cocaine,” Pastor Engel said. “Most of them are environmentally contaminated by violence, drugs and domestic violence, and this trauma has not been addressed, leading to the use of different types of substances just to reduce brain trauma.”

Certain fire mediators actively intervene in gang conflicts, strive to talk to the gangs together, and negotiate a temporary ceasefire among fighting factions. Supported by charitable donations, the program includes a rehabilitation plan designed to help former gang members overcome their addiction and find employment. Pastor Engel said the ceasefire program rehabilitated 168 “high risk” gangs.

One of the reformed gang members is Wesley. Wesley was revengeful to joining the ghetto children at age 12. He spent 18 years as a gangster, becoming the “right arm” of a gang leader, during which about 30 friends were killed. Today, he has turned his life around and is praised by his community. “The community knows your story, you know your past, and only respects you when you turn around,” Wesley asserts, “They won’t judge you anymore.”

Challenge and undoubted hope

Despite these deep individual successes, ceasefires face serious hurdles. The program was crippled by cuts in funding from cities, forcing dedicated conflict negotiators to work voluntarily, balancing street work with the need to support families. Popular violence remains a lasting challenge, and peace rarely lasts more than a few days in Hanover Park. Even during delicate ceasefire negotiations, tragedy can be hit with many women and children killed by bullets of straying.

Still, Pastor Engel and his team are pushing to not succumb to the constant threat of set-offs and violence. “People near me have died of this gang violence… my own stepbrother was shot in this gang violence,” he shares, but insists that “I didn’t quit this job.” He acknowledges the “fear” and “anxiety” that disrupts society, but is driven by a “cause.”

The overwhelming message from both the community and the Rev. Engel is one of independence and indomitable resolve.

“No one comes from local government, not from overseas, not from overseas, not from overseas, not from anywhere to save us. No one brings a magic wand to heal the Cape Flat.