The Committee on Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Language Communities in South Africa (CRL Rights Committee) has announced the establishment of an independent committee aimed at ensuring that the religious sector of the country maintains its dignity and maintains order.

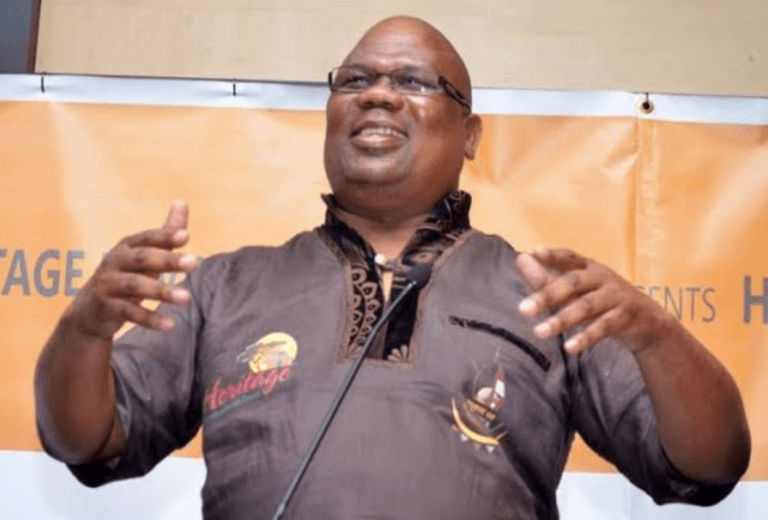

The establishment of a Section 22 Committee, chaired by religious and cultural expert Professor Musa Xulu, rekindled debates over the regulation of religion in South Africa. Professor Xulu described the initiative as “proactive, seeking to avoid disasters and help the Christian faith maintain its dignity.”

The committee plans to conduct basic research before it serves as a consultation agency for preparing recommendations. “Once we have completed our basic research, we are committed to fully commissioning the committee not as a church inspector, but to devising a document that gives recommendations,” Professor Xulu said. Thoko Mkhwanazi-Xaluva, chairman of the CRL committee, indicated that the committee is expected to finish its work and make recommendations by the end of 2026.

The formation of this committee is among many reports of abuse and spiritual violations within several churches across the country. The latest is the trial of Timothy Omotoso, a Nigerian televangelist from Durban, who was acquitted in the South African High Court on April 2, 2025. Trafficking and assault. CRL previously criticized the National Prosecutor’s Authority (NPA) for dealing with the case.

The committee’s stance is to “restore sector order, not regulating the pulpit.” By clarifying Mkhwanazi-Xaluva. This new focus builds on CRL’s previous research into the commercialization of religion, which began in 2017. As a constitutionally established organ, CRL is mandatory to promote the rights of cultural, religious and linguistic communities and tolerance between them.

In 2015, in response to controversial news reports about concerns about pastors and religion becoming commercial institutions, CRL launched a research study on the commercialization of religion and abuse of people’s belief systems. The study included summoning religious institutions and leaders for national hearings.

The 2017 report, which stemmed from the investigation, highlighted criminal behaviour by religious leaders and called for state intervention. It proposed stricter regulations for faith-based organizations. Some of the recommendations included requiring religion to have a significant number of followers with a religious text of defined or ancient origin. The Religious Peer Review Committee also suggested that on behalf of the entire religious community, general religious practitioners should be approved.

CRL proposed amending the CRL Act to allow for self-regulation by the religious sector through a structure that includes the Peer-Review Committee and its umbrella organization, and CRL issued a certificate of registration based on recommendations from these bodies.

However, these previous proposals faced important opposition. For example, South Africa’s Religious Freedom (in the case of SA) described the CRL’s plan as a “serious existential threat” to religious freedom. Michael Swain, executive director of SA, argued that state powers to define religious leaders or legal organizations undermine core democratic principles. He pointed to examples of other African countries such as Rwanda, Angola, Namibia, Uganda and Kenya.

Rwanda closed more than 5,600 churches in July 2024 after nearly a third of the places of worship inspected failed to meet legal standards. Rwanda is gradually implementing the law passed in 2018 to regulate religious groups. In Kenya, the task force established by Kenya’s President William Root recommended a hybrid regulatory framework that would pass large surveillance to the government to reduce the spread of cults and financial predatory practices common in several churches.

Critics of the CRL direction argue that existing laws are sufficient to address abuse and crime within the religious sector. They argue that criminals should hide behind religious freedom and face the full power of the law. It cites the successful prosecution of Recebo Lavarago, “The Prophet of Fate.” According to this perspective, the real problem is not the lack of regulations, but the lack of enforcement of existing laws. It also raised concerns that the new monitoring structure itself could lead to corruption.

Law scholar Dr. Emma Charlene Levare highlighted the risks of regulating religion elsewhere in Africa citing article 18 of Article 18 of the South African and South Africa International Contract (ICCPR) (such as International Human Rights Law that Guarantees Thinking, Conscience, and Religion Rights (ICCPR).

This right includes absolute freedom to hold beliefs and freedom to show that belief, regardless of how others find it “odd.” Although the manifestation of religion may be limited, such restrictions must be stipulated by law and be necessary to protect public safety, order, health, morality, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

Some people argue that some of the previous CRL recommendations, such as demanding theological degrees and allowing peer review organizations to determine what is “normal” or “unusual” for their beliefs, may hinder the absolute right to retain beliefs and overly restrict the manifestation of religion.

The idea that religion must have ancient texts can discriminate against new or non-traditional religions. The CRL says its recommendations promote self-regulation, but the proposed structure places the CRL as the final arbiter.

The Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Cooperative Governance and Traditional Issues (COGTA) previously rejected CRL’s stricter recommendations in 2018 and acknowledged widespread opposition from the faith community. COGTA recommends self-regulation by religious organizations and suggests the adoption of codes of ethics. This led to the creation of a code of conduct based on the Religious Freedom Charter, which had gained great support from people of faith for SA Note.

The establishment of a new Section 22 committee by the CRL Rights Committee shows the continued efforts to address issues within the religious sector. However, it remains to be seen how by 2026 the committee’s work and final recommendations will navigate the complex balance between protecting citizens from potential abuse and supporting the fundamental right to religious freedom in South Africa.